The Encyclopaedia: A-F

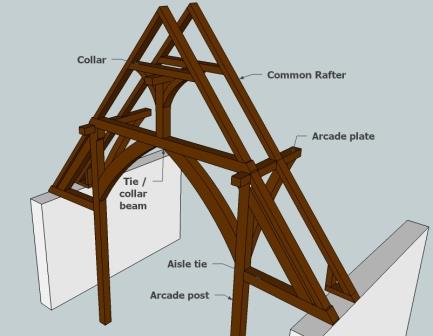

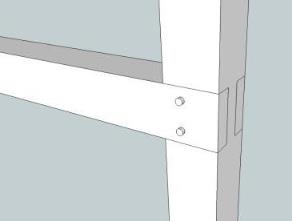

| Aisled Construction: | As found in an aisled building, viz. a structure having a central longitudinal space (in ecclesiastical buildings a nave) and one or two, usually narrower, outer longitudinal spaces (aisles). These spaces are usually divided from each other by aisle posts and often arcades. See illustrations below. |

|---|

| Aisle Tie: | Transverse timber connecting wall plate with arcade post in an aisled structure; see Fig. a, above. |

|---|---|

| Arcade Plate: | In aisled construction, longitudinal timber, square-set (to the ground), into which the arcade posts and the tie-beams are framed; see Fig. a. |

| Arcade Post (aisle post): | In aisled construction, vertical timbers carrying arcade plate and tie-beams. Corresponds to masonry piers in the arcade of a masonry structure; see Fig. a. |

| Arch Brace: | Curved brace; forms an arch when paired. Called 'archebras' at Gravesend in 1375, and 'archbandes' at York in 1434.

The roof of St John’s Church at Bury St Edmunds in 1439 was to be carpentered with 'vi pryncepal couplys archebounden.'

Literature: Salzman (1952).

|

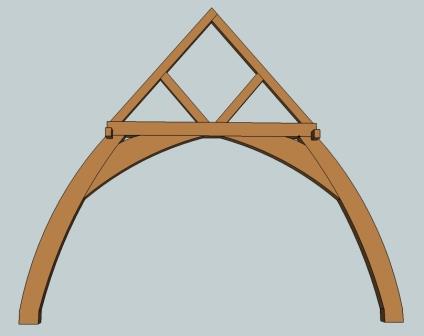

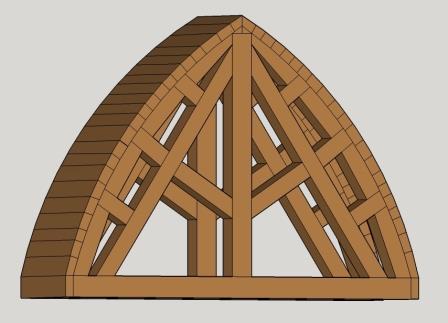

| Arch-braced Roof: | A display roof composed of untied principal frames; the principal rafters are arch-braced to a collar and/or a wall post or wall plate; see illustration below: |

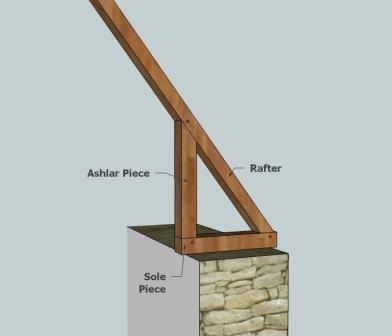

| Ashlar Piece: | Vertical timber at the rafter foot forming a triangle with the common rafter and the sole piece. See foot of rafter below. In medieval documents referred to as 'aschelers', 'asshelers' or similar.

Literature: Salzman (1952).

|

|---|---|

| Baines, Sir Frank: | (1877-1933) HM Office of Works architect;

Chief Architect for the major restoration of the Westminster Hall hammer-beam roof (carried out 1913-22), and, during the same period,

the hammer-beam roof of Eltham Palace Great Hall. Baines solved the dangerous condition of both structures by inserting massive amounts of steelwork.

Baines was an astute analyst and interpreter of these roofs. His Report... on the condition of the roof timbers of Westminster Hall (1914) is indispensable for anyone wanting to understand Hugh Herland's masterpiece. |

Detail of apex showing steelwork inserted under the direction of Frank Baines during restoration c. 1913.

| 'Balle's Place': | Merchant's House (now destroyed) in Salisbury which contained one of only a handful of C14 hammer-beam roofs.

It was a structure of considerable visual sophistication. But after being dismantled in 1962 for possible re-use, it was scandalously left to rot

in a municipal yard.

Literature: Beech (2015); Bonney (1964).

|

|---|---|

| Base Cruck | Transverse frame in which pairs of heavy curved timbers - cruck blades - rise from ground-level to a tie beam or collar. Medieval carpenters used this construction as an alternative to aisled construction to broaden the internal space. The advantage of the base cruck is that it does not require arcade posts, so the internal space remains clear (cf. 'Crucks' below). |

| Beam: | Major horizontal timber, having a load-bearing and/or tieing function; archaically (and poetically) known as a 'summer.' |

|---|---|

| Beeston-next-Mileham, Norfolk: | The nave of the lonely church on the edge of the village contains a fine hammer-beam roof.

Dating to probably c. 1410, it is a superbly proportioned roof of collarless construction. Principal frames of unusually long wall posts alternate with intermediate

frames sans wall posts with 'panel' hammer-beam figures. The long wall posts serve to accommodate holy figures (all sadly defaced

during some iconoclastic purge). The north aisle is also blessed with a hammer-beam replete with carved figures. Carving is exquisite and of consummate craftsmanship throughout. |

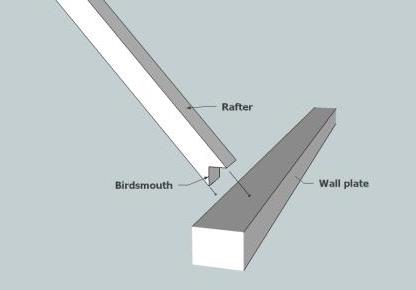

| Birdsmouth Joint: | Notch cut into the end of a timber to accommodate the arris of the timber to which it is framed; see below. |

|---|

| Boxford Church Suffolk: | In all likelihood the oldest timber porch in England, the north porch of St Mary's

is an amazing survivor. The Decorated tracery of the two-light side windows stylistically dates the porch probably to the early fourteenth century. The carpenter evidently intended the tracery to mimic the work of the mason, and this is the ethos behind the whole structure. The bay 'piers' (timber posts) are buttressed - on the front corner posts the buttressing is diagonal. Inside, triple shafts engage the 'piers' and rise to bell capitals, from which spring the ribs of timber vaulting. The webbing is now gone, but when the structure was intact and painted, the intent was to deceive the eye, for the observer to apprehend carpentry as masonry. And yet the carpentry here is consummate, the craftsman going to inordinate lengths to pull off his deception - and consequently hide his own craftsmanship. For instance, the piers and buttressing, the shafts and their capitals, are all fashioned from single timber posts: in other words, all elements comprise a single timber. The amount of labour involved to carve the posts like this was extraordinary. The beam forming the door head is cranked, prosaically allowing greater headroom, aesthetically permitting a more pointed Gothic arch. Inside, the vaulting is complex, composed of lateral ribs, diagonals, ridge and even tiercerons. Labour was saved, however, when the carpenter formed the tracery. The mason would have assembled his tracery from individual components. The carpenter cut his from two or three broad boards laid horizontally on edge. Often unnoticed, Timber vaulting is surprisingly common in medieval architecture. Although rabidly condemned by later critics such as John Ruskin as an immoral deception, many English cathedrals contain vaults which, apparently of stone, turn out to be timber. The nave of York Minster is an auspicious example of this technique. At almost 50ft (15.2m), the nave is the widest of any English cathedral, and the span probably prompted the builders to adopt carpentry rather than the more thrusting, heavier masonry. Boxford provides a fine opportunity to study how the fourteenth-century carpenter went about constructing timber vaulting - albeit in miniature. You can see his intersections between the various ribs and, stand on a box, his handling of the springing. Literature: (on moral 'delinquency' of timber vaulting) Pugin (1841); Ruskin (1849).

|

|---|

| Brace: | Timber usually set between vertical and horizontal members to provide triangulation. |

|---|---|

| Bradford on Avon Tithe Barn: | Monastic stone-walled barn. Its spectacular timber roof has been tree-ring dated to 1334-79.

For Historic England the roof is of cruck construction, with 'two true crucks and eleven two-tier crucks.' For the ADSDD, the roof has 'raised arched trusses, of … three types, with uncontinuous [sic] principals supporting three purlins.' On my visit I didn’t realise such disagreement existed, so I would have to return to pronounce yea or nay. My impression was that it was nothing other than cruck construction, and checking Pevsner, he agrees. What we can be sure of is that it is of 14 bays, measures around 168 x 30ft (51.2m x 9.14m), and has three tiers of arched wind braces typical of the first half of the fourteenth century. Anyway, forget the details - just crane your neck and marvel. |

| Bredon Barn: | Awaiting entry |

|---|---|

| Bressummer: | a: Major horizontal timber, carrying joists and vertical components; often applied to the main timber running the length of a building and supporting a jetty, illustrated here. b: A lintel. |

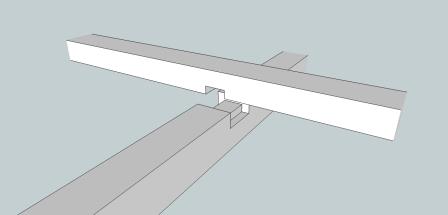

| Bridle Joint: | The negative of a mortice and tenon joint. Solid timber replaces the mortice and two adjacent housings are cut; the tenon is absent but the tenon cheeks remain; see illustration below. |

| Bury St Edmunds St Marys Church: | Dating to around 1430, St Mary's holds a contender for the finest East Anglian hammer-beam roof. In structure: principal hammer-beam frames alternate with arch-braced frames, a not uncommon arrangement. Relatively slender hammer posts are arch-braced to the principals; from this point a further arch brace rises to the lofty collar. Long wall posts accentuate the sweep of the uninterrupted arch in the intermediate frames, and of the trefoil in the principal frames. The main joy of Bury though is its sumptuous medieval sculpture, and really the Bury carpentry exists as a surface for carved ornament. Relief and figure carving abound, and of superb craftsmanship, on a par with work at Mildenhall. In each cross-frame, the hammer-beam figures are paired in opposition, and various attempts have been made to identify and interpret the individualised figures. At the east, most holy, end are the Virgin Mary and the risen Christ (contested by some scholars!). The rest of the angels are dressed as clergy and their assistants vested for the celebration of high mass, or perhaps participants in the popular late-medieval celebration the Coronation of the Virgin. Some bear chalices; others censers, candlesticks and gospel books. Subsidiary carving is of even finer quality. The cornice carries two tiers of demi angels, again individualised. The wall posts house forty-two figures of saints and prophets sheltered by carved capitals: St Joachim carries a basket of turtle doves; St James the Great on pilgrimage, with his pilgrim's hat, travel pouch and staff, toes clearly peeping out from his sandals; St Simon (or possibly St James the Less) bears the saw of his martyrdom, as does St Andrew with the saltire; St Michael skewers his dragon. In the darker corners of the roof stranger entities lurk. Wolves, cats and apes preside. A naked doctor proffers a flask - a quack? At the east end, between the Virgin and the risen Christ, and in typical medieval juxtaposition of the sacred and profane, a pair of naked, hirsute, woodwose emerge from the forest wielding clubs. Take your binoculars with you and prepare to spend an hour or so exploring this magnificent roof - one of the outstanding works of English medieval art. And there's a fourteenth-century waggon roof in the chancel.

Literature: Tymms (1845-54); Beech (2015).

|

|---|

| Butt Purlin: | See 'purlin.' |

|---|---|

| Carbrooke Church Norfolk: | A splendid medieval nave roof, carpentered by a craftsman interested as much in form and ornament as in keeping the rain out. Essentially it is a collarless arch-braced roof, and the lack of collar means that the arches can soar almost to the apex. The structure is facilitated by the carpenter’s use of 'king pendant' timbers framed into the ridge. The king pendant also permits the ridge to be arch-braced, producing a subtle arcaded effect high in the roof. Rather stiff carved wall-post and hammer-beam figures - of no structural value - further adorn the roof, as do giant foliate 'bosses' of uncertain date.

Literature: Beech (2015); Mortlock & Roberts (2007). |

| Carow, Robert: | (fl. 1491-1531) Oxford Carpenter. Interesting mainly for the inventory of his goods made after his death

which lists some of his tools:

5 chisels; a compass and 2 augers; a gouge; an old chipping axe; 2 drawing planes; 13 small planes; 2 adzes; a handsaw; a drawer and 7 small planes;

a square; a hammer; a wimble; 2 prickers; a knife and a compass; a small grindstone.

Literature: Harvey (1975 & 1984). |

|---|---|

| Carpentry: | Structural timber work, in contrast to 'joinery' which is concerned with ancillary components such as windows and door frames. | Centering: | Centering: Bread-and-butter work for a carpenter engaged to work on any high-status building, or masonry structure

requiring arches - a bridge for example. Centering is the temporary structure used to support an arch during its construction. Once the arch

is complete and self-sustaining and the mortar has, at least to some extent, gone 'off', the centering can be 'struck', or removed.

Centering had been used for centuries to sustain relatively simple tunnel and groined vaults. During the Gothic age, however, from around 1160 onwards, the pointed rib vault became the dominant form, and for the carpenter, with their intersecting ribs and multiple planes, this was a more challenging proposition. With the eventual inclusion and multiplication of tierceron and lierne ribs, vaults became highly complex, demanding a corresponding complexity from the carpenter's centering. And not all vaulting was orthogonal in plan. The challenges involved in designing the centering for a trapezoidal bay, for example in the curve of an ambulatory, were immense. Here, compound angles, always a headache for the carpenter, abound. Peter Nicholson (1765-1844) was one of the few early writers on carpentry to tackle the subject of centering and 'cradling of groins.' As well as apsidal vaults, among other sophisticated structures Nicholson discusses are 'under pitch' groins, in which intersecting lateral vaults are lower, and 'ascending groins', for instance, those which follow a staircase. In ten pages of drawings baffling to the layman - and only slightly more illuminating text - Nicholson explains how to lay out such complex carpentry. A high degree of geometrical skill was required to devise such plans, and much study and practice would have been required for the carpenter to become proficient in both design and execution. But proficient the medieval carpenter became. Bread-and-butter work it may have been, but the construction of centering demanded that the craftsman carpenter bulky timbers into a state of high precision, and position them meticulously often at a dizzying height. The subsequent stability of the vault depended on such precision. The mason then merely placed his voussoirs, precisely cut, possibly to a pattern made by the carpenter, on the carpenter's elaborate but ephemeral structure. Technical advances in vaulting must have depended to a large extent on the creativity of the carpenter. Yet the development of Gothic vaulting, recognised as one of the great artistic achievements of the late medieval period, is invariably credited to the mason. Vaulting must, however, have followed the form given to it by the carpenter.

Literature: Nicholson (6th ed., 1814); Tredgold (1871); Ellis (1927); Salzman (1952); Fitchen (1961); Acland (1977); Beech (2015).

Art: Pieter Bruegel, The Tower of Babel and The 'Little' Tower of Babel, (both c. 1563). |

| Chest: | Medieval survivors are found in some parish churches. Below is an example from St Michael's, Alnwick, said by Pevsner to be early C14 Flemish on stylistic grounds.

More to follow. |

|---|

| Chichester Cathedral: | The roofs over the nave and choir of Chichester Cathedral, dendro-dated to the last half of the thirteenth century, are hugely important. Here the carpenter framed-in a number of features which, when combined, make his structures highly unusual in English medieval carpentry and difficult to categorise: long crown posts jowled to support a high collar and collar plate; parallel(ish) rafters; side-struts from crown post to rafter clasping side-purlins via a jowled termination; braces from side strut to purlin (to prevent purlin sag). Scholars have seen French influence in these atypical roofs, and indeed, the chancel roof of Amiens Cathedral (1284-1305d) and a barn at Maubuisson (Seine-et-Oise), believed to be of a similar date, both contain strikingly similar carpentry. The use of side struts (crown post to rafter) foreshadows similar carpentry in the king-post roofs of post-medieval England, a type of roof construction which was to become ubiquitous in the eighteenth century, and which is still common construction today. Was the Chichester carpenter a prescient craftsman, experimenting with techniques that were only to become common practice four centuries later? The internal span is around 27ft (8.23m) and the pitch is 54 degrees.

Literature: Munby (1981). The illustration below is based on those in that article.

|

|---|

| The Bishop's Kitchen. A stone's throw from the cathedral, the Bishop's Palace contains what is probably the earliest hammer-beam roof. The roof in the former kitchen has been tree-ring dated to 1293-1320, and documentary evidence places it to the earlier end of those parameters. The carpentry is analogous to that of St Mary's Hospital, of a similar date, a quarter of a mile to the north-east. |

| Clasped Purlin: | See Purlin |

|---|---|

| Clenchwarton, Simon: | (fl. 1442-61) Carpenter, King's Carpenter to Henry VI from 1451. |

| Cleobury Mortimer Church: | St Mary's has much to interest the aficionado of medieval carpentry. Fine fifteenth-century roofs in

the nave and chancel, and perhaps, most interestingly, one of the oldest UK roofs in the south porch. Here is a small common-rafter roof stuffed with

interesting carpentry techniques. For example, curved ashlars and soulaces which would have formed a Gothic arch when boarded over.

This Shropshire roof was carpentered around the time King John signed the Magna Carta - between 1212-42.

Literature: ADSDD.

|

| Coffin: | The medieval carpenter could turn his hand to any task.

See the two very early examples below, hewn out of logs—which seems like an awful lot of work. |

| Cogged Joint: | Type of lap / housing joint with a central raised section; see below: |

|---|

| Coke, Humphrey: | (fl. 1496-1531) Coke's gravestone is inscribed thus: 'Citizen and Carpenter of London, and Master Carpenter of all the works to our Sovereign Lord King Henry VIII.' Coke was appointed King's Carpenter in 1519, and he proved to be the most gifted and prolific craftsman of his age. He is first heard of at the end of the fifteenth century, working for Henry VII on works at Berwick Castle. He went on to work extensively on prestigious projects at Eton College, in various Oxford colleges and at Henry VII's expression of piety, the Savoy Hospital near Charing Cross in London.

Coke, however, was no horny-handed illiberal 'mechanic.' He was a designer and draughtsman of some repute, repeatedly being paid for his architectural plans. The founder of Corpus Christi College Bishop Fox wrote: 'He is righte cunnynge and diligente in his werkes ... if ye take his advise ... he shall advantage you ... in the devisynge as in the werkenge of yt.' It seems Coke was an admirer the hammer-beam roof. He employed his cunning and diligence to carpenter ornate examples in the Savoy Hospital (c. 1515), and at Oxford, in halls at Corpus Christi for Fox (1516) and at Christ Church for Cardinal Wolsey (c. 1529). It is possible that Coke also designed the hammer-beam now at Braenose College Chapel, now concealed by plasterwork. John Harvey called the Christ Church roof: 'the last great work of medieval carpentry, uncontaminated by Renaissance influence.' The low-pitched hammer-beam is difficult to pull off, but this is indeed a majestic roof, consummate in design and carpentry, redolent both of Westminster Hall and Eltham Palace hall. Constructing the roof for Wolsey just before the Cardinal's demise and the onset of the Reformation, Coke was the last great English medieval carpenter. Literature: Smith (1736); Colvin (1975); Harvey (1975 & 1984)

|

|---|---|

| Collar: | Horizontal, transverse timber connecting either common or principal rafters above wall-plate level; see Fig. a.

In medieval documents collars are usually called 'wyndebemes' or a similar derivative - an indication that carpenters thought that this timber counteracted lateral wind forces. In reality, diagonal bracing timbers, such as soulaces and scissor bracing more efficiently serve this purpose. Collars primarily prevent the rafters from sagging under the weight of the roof covering. Literature: Salzman (1952); Yeomans (2009).

|

| Common Rafters: | Inclined timbers of uniform scantling that directly support the roof covering. Smaller in section than principal rafters. |

| Common rafter Roof: | Roof without principal rafters and purlins composed entirely of common rafters as inclined members. |

| Conversion: | The process of obtaining useable building timbers from a growing tree. |

| Cotton Church, Suffolk: | Fine double hammer-beam in the nave of St Andrew's - and of rare construction.

The hammer posts are of the pendant type, and are rotated 45deg so that they are framed 'arris-first' into the hammer beam. Structure

is therefore compromised, and it seems the hammer-beam framing is largely decorative and dangling from the principal rafters.

A very similar roof is not far away at Tostock and is possibly by the same carpenter.

Dendrochronology failed at Cotton, but the roof is believed to date to the 1470s. While you are there, sight up the walls. They are scarily out of plumb!

Literature: Arnold & Howard (2012); Beech (2014 & 2015).

|

| Cressing Temple | Awaiting entry. In the meantime pay Cressing Temple a visit. |

|---|---|

| Crown Plate | Longitudinal timber supported by a crown post (see below), and lying below the collar, sometimes called a collar purlin. Carpenters braced the crown plate to the crown post, probably intending such framing to work as a racking preventive.

Literature: Brunskill (2007); Yeomans (2009).

|

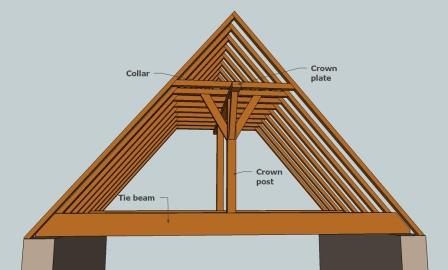

| Crown-post Roof: | An important roof type of the medieval period. See illustration below. The central vertical timber is the crown post. No principals or purlins are included in a crown-post roof, the common rafters being supported by collars. As well as an important structural type, the crown-post roof developed an ornamental and display function, and is found in many high-status buildings. |

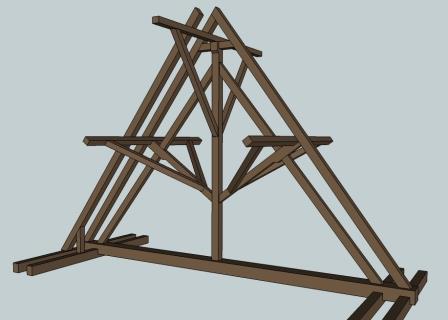

| Crucks: | Heavy curved timbers, 'blades', set in pairs, rising from ground level towards the apex of a structure, forming

a simple A-frame construction (see illustration below). To complete the structure, ancillary timbers are added,

for example purlins and wall framing. Many variations on this basic theme exist.

Cruck construction forms an autonomous and fascinating field of study beyond the scope of this work. Literature: Alcock (1981).

|

|---|

| Debenham Church, Suffolk: | The prosaic roof in the nave of St Mary Magdalene's is, nonetheless, notable. Tree-ring dated to 1397-1409, it is the earliest post-Westminster Hall roof yet discovered to feature hammer beams. Holy figures were once morticed onto the ends of the hammer beams |

|---|

| Display Carpentry: | awaiting entry |

|---|---|

| Double-Framed Roof: | Roof with principal rafters and purlins. See illustration here |

| Dragon beam: | Horizontal Timber framed diagonally into ceiling timbers to carry the conjunction of two jetties, or framed into wall plates to receive a hip rafter. |

| Dragon Post: | Corner post supporting the conjunction of two jetties meeting orthogonally. The post is sometimes flared or jowled at the top to support the overhang, and a tree would have been selected specifically for this purpose.

Literature: Charles (1995). |

| Draw Boring: | A technique to ensure a tight fit of the shoulders of a mortice and tenon joint. The peg hole in the tenon is offset, towards the shoulder, with respect to the peg hole in the morticed timber. The offset ensures that once the peg is driven home, the joint is pulled together. The technique also serves to compensate to some extent for future shrinkage of green timber. |

| Durn: | Awaiting entry |

| Earl Stonham Church, Suffolk: | One of the great East Anglian hammer-beam roofs. Probably late C15.

Construction: a single hammer-beam roof, the hammer beams carved as angels (later decapitated); in the principal frames, conventional hammer-beam carpentry (the post standing on the end of the beam) alternates with pendant-post carpentry. Cambered collars carry king posts and, below, pendant bosses. The carpentry frames a Doom above the chancel arch. The church is aisless, but nevertheless has a clerestory — much to the benefit of the height and illumination of the roof. Much like St Mary’s at Bury, the carpentry exists as a surface for carving, and the roof is crammed with it. Birkin Harward counted over 200 different figure carvings. They include green men, grotesque heads, fools, fabular figures, dragons and an actor; the quality is exuberant and earthy. In this highly ornamental roof, even the common rafters are moulded. Another one for the binoculars and a high-powered torch. Literature: Beech (2014); Haward (1999); Knott, www.sufolkchurches. |

More photos Here

| Eltham Palace: | The Great Hall at Eltham contains one of the few fifteenth-century hammer-beam roofs sheltering a

secular space. Carpentered, probably by Edmund Graveley, for Edward IV between 1475 and 1479, the roof is a riot of ornament and visually

spectacular. Structurally, however, it must be one of the most incondite* roofs ever carpentered for a high-status client. For a long period it

was reckoned fit to shelter, not grandees, but agricultural paraphernalia.

The pendant hammer-post framing is structurally illusory and previous observers have concluded that the entire hammer-beam framing is redundant, suspended from the principals. If so, then the hammer-beam framing, pulling down on the principals, must be exerting tremendous thrust. And, indeed, it turns out such framing hasn't done the masonry any favours. A moment's monocular sighting up the internal face of the wall confirms that it has been significantly pushed out of plumb. By the beginning of the 20th century the roof was in such a dilapidated state that HM Office of Works had to perform extensive and invasive repairs. It was not, as at Westminster Hall, the appetite of the death-watch beetle which had done for the Eltham roof. It was the poorly conceived carpentry. At Eltham, Graveley decided that form and ornament should triumph over structural security, and you don't have to peer too hard to discern Frank Baines's steelwork holding it all together. *'Incondite' is a great word: 'not well put together', 'poorly constructed.'

Literature: Dunnage & Laver (1828); Morris (1871); Cescinsky & Gribble (1922); Crossley (1951); Beech (2014 & 2015).

|

|---|

Probably carpentered by Edmund Graveley.

| Ely Cathedral: | One of the great masterpieces of English medieval carpentry, the lantern over the crossing of Ely Cathedral,

is briefly discussed below under the entry for William Hurley, but Ely contains other fine examples of medieval carpentry.

The nave contains a single-framed (sans purlin) scissor braced roof of around 34ft (10.36m) in span and a steep 58deg pitch, tree-ring dated to 1237-40.

The roof was visible until it was boarded over in the mid nineteenth century, its rafters causing consternation to some viewers:

'The visitor is disappointed at seeing nothing but a set of rafters, which at so great a height appear not more substantial than those of an ordinary parish church or dwelling house ... Surely these solid walls and massive arcades were intended for a nobler purpose.' (Garland and Winkles, 1838) Often going unnoticed by visitors, the central transepts are sheltered by a pair of exquisite angel hammer-beam roofs of collarless king-pendant construction, tree-ring dated to 1426-27. The spans are big, at around 33ft (10.06m). The choir is adorned by stall-work dated to 1341-42, and so probably by William Hurley. A high proportion of the misericords are original. |

|---|

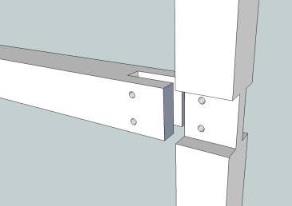

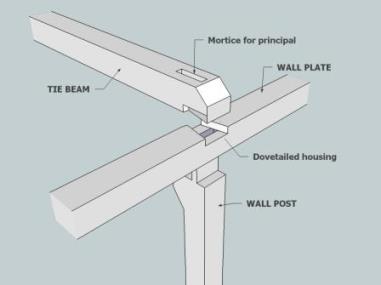

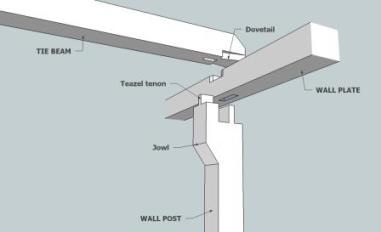

| English Tying Joint ('normal assembly'): | Four-way (with principal) configuration found at the top of a wall post. Commonly found in late medieval and post medieval framing; see illustration below (cf. reversed assembly). |

|---|

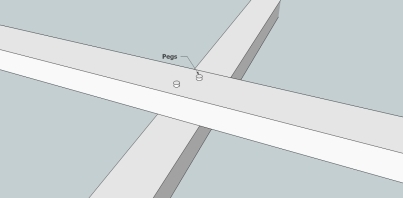

| Face Pegging: | Simple and relatively weak technique for joining overlapping timbers merely by pegging; see illustration below: |

|---|

| Fiddleford Manor Dorset: | Awaiting entry |

|---|---|

| Foot (of rafter): | Triangulated configuration at the base of the rafter consisting of ashlar piece, sole piece, rafter; see below: |

| Frame (verb): | To construct; to carpenter (eg: 'the roof was framed in 1468'); to joint (eg: 'the hammer post was framed into the rafter'). Such usage goes back many centuries (see Salzman (1952), p.579, for an example from 1532), and it is still common terminology among English 'framers' (traditional carpenters) today. |

|---|---|

| Fyfield Hall Essex: | Awaiting entry |